The Bird Hat: “Murderous Millinery”

By Jeanmarie Tucker

Over the summer I have processed only a handful of the hats here at the Maryland Historical Society (MdHS). I was drawn to one hat that I found particularly interesting. Over the summer I have had the opportunity to learn how each costume has a tie to history.

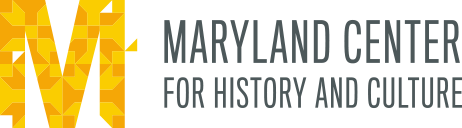

Pictured here is a black velvet hat with a small round crown. A taxidermied bird with golden-yellow and brown feathers rests on top of the hat. The bird has a tail of long white and brown plumes. Around the bird’s beak are iridescent green feathers. The bird is attached with a black wire and covered in a beige veil. One faux eye is missing. A black net veil is attached to the front of the hat. The veil would drape over the face when worn. The hat is lined with black silk faille fabric and has a plastic comb to secure the hat into place. The hat was gifted to the museum by Mrs. Alexander Rondell who wore the hat in the the 1940’s. The hat tells the story of the plume trade debates. The reintroduction of the feathered hats in America resulted in a large consumer market for feathers by millinery workers. Millinery is a term used for hat makers. The larger market for feathers instigated movements in bird conservation and preservation in the United States.

The Introduction of the Birds of Paradise into European and American trade

The bird on the hat is a Greater Bird of Paradise, also known as the Paradisaea apoda, because of its golden- yellow wings, iridescent green feathers around the neck, and its beak length. Specimen of the bird of paradise were brought to Europe in 1522 from Indonesia by the last survivors who completed Magellan’s expedition around the globe.(1) Five “Trade Skins” or prepared specimens, ignited a fascination with the bird of paradise’s beauty. Stuffed birds of paradise were not used originally as fashion ornament, but as objects of discovery and science for European cabinet collectors. Cabinet collectors attained their specimens from new-forming plume trade routes from either Indonesia or New Guinea. These collectors kept stuffed birds within carefully curated shelves for display and natural science studies. Since the Victorian era, taxidermy bird was an artistic and aesthetic process of capturing the beauty of nature for study. According to Pierre Belon’s Natural History of Birds, by the end of the 1540’s mounted birds of paradise were “a common sight in the cabinets of Europe and Turkey.”(2) The bird of paradise unfortunately were not admired by naturalists only.

Right: Collection of Foreign Birds, After Leroy de Barde, 1810

Right: Collection of Foreign Birds, After Leroy de Barde, 1810Left: Victorian taxidermied bird dome.

The Bird Hat Fashion

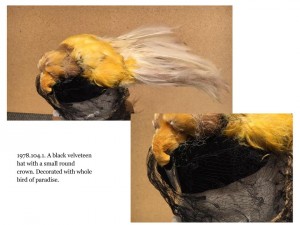

Right: Ladies with hats: one of them with taxidermy (whole bird), as was quite typical for this period. Shorpy Historical Photo Archive :: Sisters: 1895. Victorian Millinery.

Right: Ladies with hats: one of them with taxidermy (whole bird), as was quite typical for this period. Shorpy Historical Photo Archive :: Sisters: 1895. Victorian Millinery.Left: Print from glass negative, ca. 1898. Young lady in feathered hat.

The January 18, 1868, issue of Harper’s Bazaar in the “New York Fashion” section states:

A few of the feather and fur bonnets, now so fashionable in Europe, have just been imported. The feathers used are those of the grebe and pheasant. The white and pearl gray grebes are bound with green, scarlet, or blue velvet, while bonnets of dark pheasants’ feathers have a fall of brown lace … ” (3)

This issue of Harper’s Bazaar announced the emergence of a new type of bonnet and hat style in Europe arriving to America- the bird hat. Feathered hats have decorated women’s heads since earlier centuries. In the 15th and 16th centuries, noblemen donned peacock and ostrich feathers on helmets as a sign of class and status since feathers were rare and expensive.(4) Because feathers were a major status symbols, laws were created to prohibit the lower class from wearing them. Later, Marie Antoinette reintroduced the feathered headdress into fashion. The story states that in a sudden moment, Marie Antoinette placed an ostrich and peacock feather in her hair one evening, and then after the King admired and praised the plumes, created a trend throughout the court.(5) Although plume-trimmed hats have been in western culture for a long history, it was not until the late nineteenth century that lavishly decorated feathered hats become commonplace.

The Plume Trade

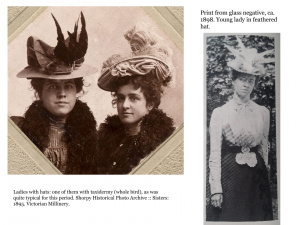

1910 black horsehair lace, stretched over a wire frame decorated with a whole bird of paradise, labeled James G. Johnson & Co. Newark. New Jersey.

1910 black horsehair lace, stretched over a wire frame decorated with a whole bird of paradise, labeled James G. Johnson & Co. Newark. New Jersey.In Europe and America, hats were seen decorated with birds wings, heads, plume or whole bodies towards the late 19th century. Termed “fancy feathers” in the August 20, 1879 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, the most fashionable hats were composed of these “fancy feathers” plucked from the rarest birds.(6) Feathers from rare birds gave its wearer great prestige. As a result, bird of paradise plumes were very desirable because of their rarity “resulting expense in Euro-American plume markets.”(7) It is estimated that about 30,000-80,000 bird of paradise trader skins were sold annually in feather auctioned in London, New York, and Paris between 1905 and 1920.(8) Hats were not the only fashion to use bird of paradise plumage, as this fan decorated with the head of a Bird of paradise shows.

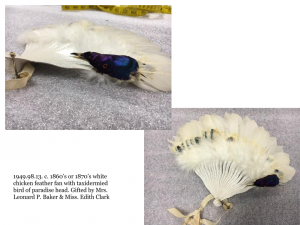

1949.98.13. c. 1860’s or 1870’s white chicken feather fan with taxidermied bird of paradise head. Gifted by Mrs. Leonard P. Baker & Miss. Edith Clark

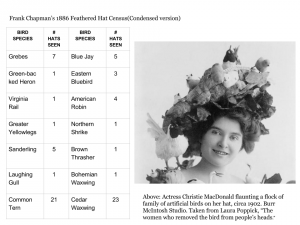

1949.98.13. c. 1860’s or 1870’s white chicken feather fan with taxidermied bird of paradise head. Gifted by Mrs. Leonard P. Baker & Miss. Edith ClarkWhile rarer species of birds were the most preferred, milliners used any species of bird to use for their creations, and did so with alarming rates. The American Ornithologist Union estimated in 1886 that five million North American birds were killed each year for millinery purposes.(9) The same year, the ornithologist Frank Chapman wrote a famous list of the birds he identified atop ladies’ hats. For two day during his walks from his uptown Manhattan office to 14th Street, the center of the women fashion district, Chapman identified 174 bird hats representing 37 different species. He recorded the “wings, heads, tails or entire bodies of three bluebirds, two red headed woodpeckers, nine Baltimore orioles, five blue jays, twenty-one common terns, a saw-whet owl and a prairie hen” to name a few.(10)

Left: Table of Frank Chapman’s 1886 Feathered Hat Census(Condensed version)

Left: Table of Frank Chapman’s 1886 Feathered Hat Census(Condensed version)Right: Actress Christie MacDonald flaunting a flock of family of artificial birds on her hat, circa 1902. Burr McIntosh Studio. Taken from Laura Poppick, “The women who removed the bird from people’s heads.”

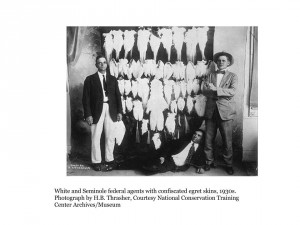

In America or oversees, the millinery industry was having disastrous effects upon native bird populations. By the turn of the 20th century, the hunting of egrets in the Florida Everglades, the wetland habitat of the egret, lead the species to the brink of extinction. Majority of egret plumes collected are obtained during the breeding season by shooting the birds as they nest. Hunters wanted to catch the largest bird nesting as larger plumes paid more. In 1903, the price for plumes offered to hunters was $32 per ounce.(11) Inevitably, the hunts resulted in the mothers of the nest being shot and the baby birds being left to slowly starve to death without their mother.(12)

White and Seminole federal agents with confiscated egret skins, 1930s. Photograph by H.B. Thrasher, Courtesy National Conservation Training Center Archives/Museum

White and Seminole federal agents with confiscated egret skins, 1930s. Photograph by H.B. Thrasher, Courtesy National Conservation Training Center Archives/MuseumThe Audubon Society

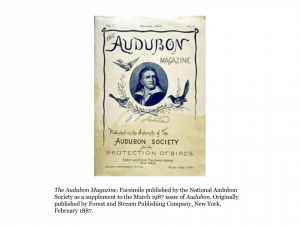

he Audubon Magazine. Facsimile published by the National Audubon Society as a supplement to the March 1987 issue of Audubon. Originally published by Forest and Stream Publishing Company, New York, February 1887.

he Audubon Magazine. Facsimile published by the National Audubon Society as a supplement to the March 1987 issue of Audubon. Originally published by Forest and Stream Publishing Company, New York, February 1887.Harper’s Bazaar announced the founding of the first Audubon Society on April 3, 1886. In the “Personal” section of the magazine appeared this notice:

“A society taking its name after the great naturalist J.J. Audubon has been established for the purpose of fostering an interest for the protection of wild birds from destruction for millinery and other commercial purposes . . .It invites the cooperation of persons in every part of the country.”(13)

The Audubon Society referred to by Harper’s Bazar was founded by George Bird Grinnell, owner and editor of Forest and Stream, and avid outdoors-man, in 1886. By 1895 the original Audubon Society had faded away, and the wearing of bird hats was as rampant as ever.

Cover Image of Kathryn Lasky . She’s Wearing a Dead Bird on Her Head! New York: Hyperion Paperbacks for Children, 1997.

Cover Image of Kathryn Lasky . She’s Wearing a Dead Bird on Her Head! New York: Hyperion Paperbacks for Children, 1997.This was not the end of Audubon Society however. A group of American women came together to debate and protest the wearing of “Murderous Millinery.”(14) In 1896 after reading an article describing the horrific murder of birds in Florida for hat plumage, Mrs. Harriet Hemenway, a well-known Boston socialite and philanthropist, decided to end the plumage trade. The now legendary story goes that she called her cousin, Miss Minna B. Hall to tea, and the two of them took down the social register, the Boston Blue Book, and proceeded to contact the most fashionable ladies of Boston in order to create a mass boycott of feathered millinery. They invited these wealthy and fashionable women to Mrs. Hemenway’s home, and over afternoon tea parties, they planned and organized their next steps. To stop the plume trade, the women agreed that they would target consumerism rather than the production of such millinery. Therefore, the people that needed to be reached with the bird protection message were the wearers of plumed hats: upper class women. Ultimately, this is a story about a social class of women that could afford to wear birds on their hats but chose not to. The Audubon Women society argued that women should be more sympathetic to the hunting of birds for the birds were similar to them; they were mother-like. The society criticized bird wearing women as being immoral and “in violation of the prescribed gender role,” illustrating the way Florida egret hunters leave the baby birds to starve.

Sanctuary, The Journal of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts, January/February 1996

Sanctuary, The Journal of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts, January/February 1996In 1900, just four years after the women of the Massachusetts Audubon Society planned their bird preservation strategies over tea, the U.S. Congress passed the Lacey Bird and Game Act. Game birds can be hunted for sport or food with regulated legal hunting seasons and bag limits.(15) Although states had protected their native populations from feather hunters and prevented the sale of feathers, bird hunters would transport the feathers to states where the birds were not native and therefore not illegal to sale. The Lacey Act prohibited interstate commerce of protected species. If charged for ‘knowingly’ transporting wildlife the fine was $500, and if caught receiving illegal wildlife the fine was $200.(16) The U.S. passed another act in 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, banning feather imports and establishing an important precedent for the Endangered Species Acts of the 1960’s and 70’s that banned the transport of state protected wildlife.(17)

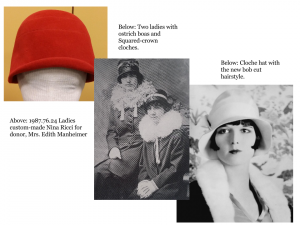

Left:1987.76.24 Ladies custom-made Nina Ricci for donor, Mrs. Edith Manheime.

Left:1987.76.24 Ladies custom-made Nina Ricci for donor, Mrs. Edith Manheime.Middle: Two ladies with ostrich boas and Squared-crown cloches.

Right: Cloche hat with the new bob cut hairstyle.

The hunting of birds of paradise for the millinery trade was finally brought to a end in the 1920s when all species of the bird of paradise were protected from export out of New Guinea. Yet, as absurd as it may sound, it was a new hairstyle that lead to the end of the deadly feather trade.(18) In the 1920’s, the bob and other short hairstyles were introduced. These short cut would not support large extravagant hats. As plain slouch hats and ‘cloches’ reached the height fashion, plume hunters were forced to abandon their trade, thus ending the plume trade and “Age of Extermination.”

[1] Kirsch Stuart “History and the Birds of Paradise” Expedition Magazine 48.1 (March 2006): 17 Accesed through: http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=1011

[2] Dr. Merle Patchett, “Fashioning Feathers: Dead Birds, Millinery Crafts and the Plumage Trade,” (2011) Acessed through: https://fashioningfeathers.info/birds-of-paradise/.

[3] “THE FEATHER TRADE AND THE FORMATION OF THE AUDUBON SOCIETY.” (March 23, 2010) Accessed through: http://www.farnsworthmuseum.org/blog-entry/feather-trade-and-formation-audubon-society

[4] Susan Langey. “Vintage Hats & Bonnets 1770-1970: Identification & Values,” (Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 1998), 11.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Amelia Birdsall, “A Woman’s Nature: Attitudes and Identities of the Bird Hat Debate at the Turn of the 20th Century,” (Haverford College History Department, April 15, 2002,) 20. Accessed Through: http://triceratops.brynmawr.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10066/675/2002BirdsallA.pdf?sequence=8

[7] Kirsch Stuart “History and the Birds of Paradise,” 16.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Amelia Birdsall, “A Woman’s Nature: Attitudes and Identities of the Bird Hat Debate at the Turn of the 20th Century,” 29.

[10] Ibid. 40.

[11] Dr. Merle Patchett, “Fashioning Feathers: Dead Birds, Millinery Crafts and the Plumage Trade.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] Amelia Birdsall, “A Woman’s Nature: Attitudes and Identities of the Bird Hat Debate at the Turn of the 20th Century,” 31.

[14] Term coined from the short article “Murderous Millinery” published in the New York Times on July 31 1898.

[15] National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. “The Feather Trade and the American Conservation Movement” Accessed July 10, 2016. http://www.americanhistory.si.edu/feather/index.htm

[16] Dr. Merle Patchett, “Fashioning Feathers: Dead Birds, Millinery Crafts and the Plumage Trade,”

[17] National Museum of American History, “The Feather Trade and the American Conservation Movement.”

[18] Dr. Merle Patchett, “Fashioning Feathers: Dead Birds, Millinery Crafts and the Plumage Trade,”