If Clothes Could Talk: The Social History of the Tea Gown

By Emily McCort, 2019 Summer Fashion Archives Intern

The tea gown has had many influences and inspirations. While the tea gown is very much a Victorian-era creation and a response to late nineteenth century culture, the tea gown also largely influenced fashion well into the twentieth century. Emerging from the wrapper with influences from the Aesthetic Movement and the Ancient Greeks, tea gowns both rejected and reflected the fashion and artistic trends of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Throughout their evolution, these gowns transformed from a comfortable at home garment to a staple of mainstream fashion.

Tea gowns derive from women’s at-home wear and were originally intended this way. There are many terms for dress worn by women in the privacy of their home, including wrappers, dressing gowns, peignoirs, combing sacques, and morning robes – to name a few. In order to avoid confusion, this paper will focus specifically on wrappers and how tea gowns relate to them.

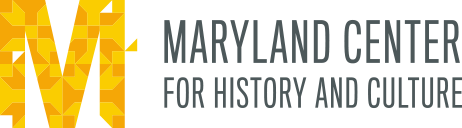

|

| Example of an 1870s wrapper. |

| Maryland Historical Society. 1971.100.2. Gift of Ms. Margery Richardson. |

A wrapper is “an informal garment (a ‘house dress’) worn at home, usually during the earlier part of the day. Wrappers fastened up the front and could be worn without a corset, making them largely unsuitable for public” [1]. Some sources stated wrappers could be worn with a loosened corset and petticoats if a woman so chose, likely because various styles of wrappers existed. The princess-style wrapper tended to be slimmer, with an elegant silhouette made from the seams of the bodice and skirt flowing into each other in one continuous line down the sides and center back. Another option was a “sacque-back” style of wrapper reminiscent of the eighteenth century dress of the same name. These wrappers would be slimmer in the front, but the back featured excess fabric pleated down the back. “Watteau” is another term used in both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for this style of dress and comes from the painter, Jean Antoine Watteau, who depicted women in this style of dress.

|

|

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”Robe à la Française. 1750–75.” C.I.54.70a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest. |

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Les Fêtes Vénitiennes, 1716-20, Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery |

Because women wore wrappers while completing chores or tasks around the home, wrappers tended to be constructed from printed cottons of bold colors and patterns. This style of fabric was not only affordable and relatively easy to replace if one had the financial means, but their busy motifs disguised soiling and the cotton could also be easily laundered and pressed.

In the 1870s, a new type of “interior dress” was added to the mix: the tea gown. Tea gowns are distinct in their ability to be both underwear and outerwear. They are different from wrappers in that “they were worn as dressing gowns around the home, but were also worn to entertain visiting female friends”[2]. The characteristics of wrappers and tea gowns are so closely interwoven, one would think that the transition from one to the other would be more gradual, or that one would replace the other over time. The key difference between wrappers and tea gowns and regular day wear is that the bodice typically lacked boning, a material usually made from baleen or metal and sewn into channels in the seams of the bodice. This purposeful exclusion provided a looser fit, a key characteristic in these garments. However, the social nature of tea gowns is what keeps them distinctly different from wrappers.

While there are still many similarities between tea gowns and wrappers, tea gowns have a much more complex history in their inception.

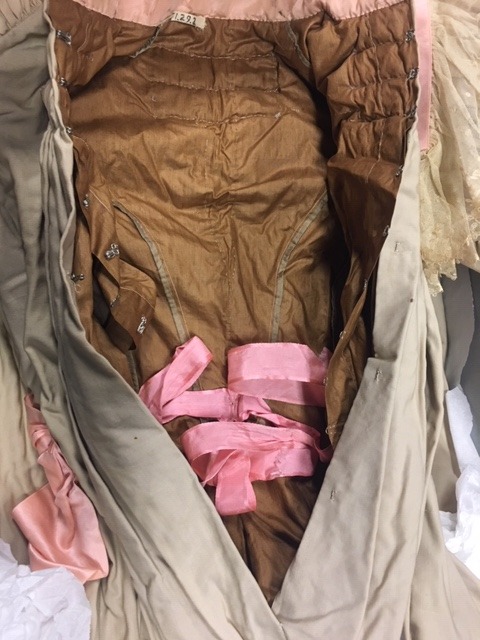

|

| 1885 Liberty Tea Gown |

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown, 1885” 2009.300.3384, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. |

In 1870, the company Liberty of London, (sometimes referenced as Liberty & Co in the 1880s), hired Edward William Godwin as the costume department’s new head, who had an interest in Aesthetic Dress and the Aesthetic Movement. These designs are one of the first mentions of tea gowns. These Liberty gowns or Liberty Dresses are distinct from other dresses of the 1870s in their use of light, pastel colors and silks. Pastel shades of green, blue, and pink were even dubbed “Liberty colors” for their use in these highly popular dresses. As will be discussed later in this paper, the Aesthetic Movement was a counterculture that gained popularity in the late nineteenth century, which had ties to the medieval period. Persons of this half of the century had a particular interest in the culture of the eighteenth century and desired to emulate it, a trend known as historicism. Liberty tea gowns drew inspiration from both of these cultural interests and their influences are defining characteristics of these garments.

Another defining characteristic of the tea gown is its response to mainstream fashion. While these gowns are typically represented as going against the tight, confining trend of day and evening wear, tea gowns often reflected the silhouettes and characteristics popular during specific decades.

|

|

|

Example of an 1875 Afternoon Dress. |

Example of an 1870s Tea Gown. |

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Afternoon Dress, ca 1875,” 2009.300.1100a, b, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown, 1875-80,” 2009.300.3856a–c, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. |

As stated before, tea gowns were created in the 1870s. As can be seen above, the waistline of the afternoon gown on the left gives the wearer a form fitting hourglass figure, while the tea gown has a shape that softly defines the waist in a much looser cut. The afternoon dress has a long train and a defined 1875 bustle, while the tea gown has a much shorter train and less obvious bustle that allowed easier mobility around the home and provided the wearer the option to go without a bustle petticoat. However, both of these gowns have an 1870s silhouette which can be seen in the shape of the skirt with its transition from the wide hoop skirt to the bustle and in the shape of the bodice (even with the softer shape of the tea gown).

Early tea gowns are relatively plain compared to their later versions, particularly when looking at 1880s tea gowns. This, in addition to their lack of boning, helps to date them.

|

|

| Maryland Historical Society, 1948.93.5a Gift of Mrs. Louisa M. Gray | Maryland Historical Society, 1951.29.2 Gift of Mrs. Edwin Broyles |

The 1895 tea gown (left) is a princess-style wrapper with boning in the bodice. The beige tea gown (right), is in the looser, Watteau style and, therefore, has no boning.

The 1880s are when tea gowns really begin to gain traction as a staple of the Victorian era. They are at their peak popularity for the nineteenth century since their introduction a decade earlier.

Tea gowns in the 1880s, “became more complex, and made from more luxurious materials – in short more lavishly feminine – and either boned inside the bodice or worn over a light corset” [3].

|

|

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown 1880s” C.I.46.63, Gift of Miss A. Gladys Peck |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Evening Dress ca 1880” 2009.300.654, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum |

In the above images, one can clearly see how tea gowns were constructed of decorated, fine fabrics and transitioned just a little bit further away from a simple lounging garment to a fashionable piece of clothing (although still worn at home). The ruffles of lace on the bodice and sleeve cuffs, as well as the longer train trimmed in black velvet are indicators of this. The gathered skirt of the tea gown merely suggests the large, shelf-like bustle popular during the 1880s and indicates the wearer’s choice to abandon the bustle.

Inspirations from the eighteenth century that were popular during this decade can also be seen in the tea gown’s striped fabric and the evening dress’s pastel, floral silk brocade.

The 1890s styles for tea gowns are particularly delightful because they reflect the drastic changes in silhouette that occurred during this decade. Historicism and the Aesthetic movement continued to influence fashion in the 1890s, but by this decade, the early nineteenth century’s penchant for Empire waists reappeared in tea gowns and some evening dresses.

|

|

| Maryland Historical Society,1984.79.5, Gift of Mrs. Lawrence K. Harper |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress 1890s” C.I.40.106.42a, b, Gift of Mrs. W. Bayard Cutting |

|

|

|

Examples of the different silhouettes available in the 1890s

The 1890s offered various silhouettes. The floral tea gown (center) dates to 1895 when gigot sleeves reached exaggerated volume, just before the Great Sleeve Collapse of 1897. The waistline of the floral tea gown is a great example of the higher waistlines inspired by the early nineteenth century. The velvet red tea gown (left), which dates to the earlier half of the 1890s, shows long, slim sleeves and the slight puff of fabric high on the shoulders serves as a predecessor to late 1890s fashion.

Reform, or radical, dress also comes largely into play in the 1890s. Reform dress was a movement in response to the ever tightening silhouettes popular in the late nineteenth century. Tea gowns are often associated with reform dress because of their looser styles.

Whether or not the owner intended it, the loose silhouette of the beige tea gown (right) makes it a perfect example of reform dress.

At the turn of the century and into the early 1900s, the frothy, feminine, light silks and fine fabrics remained a staple of tea gowns. The soft, feminine nature of tea gowns very closely mimicked the mainstream styles of this decade, particularly in the drape of the bodice.

|

|

| Maryland Historical Society, 1954.154.6, Gift of Miss Mildred Watson | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dinner dress, spring/summer 1909.” 2009.300.3223. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum |

The health concerns and push for reform dress in the 1890s appears to have made some impact. In the early 1900s, the S-shape silhouette became fashionable as a “healthier” corset alternative because it, “was designed to take pressure off the waist by shifting the force of the corset down onto the abdomen through the use of a straight center-front busk. [This] innovation [threw] the chest forward and the derrieere backwards into an almost birdlike configuration” [4].

This silhouette remained in style until the 1910s and is seen ever so slightly in the 1900s tea gown above.

|

|

| Maryland Historical Society, 1974.62.24, Gift of Mrs. William Hilles | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown, ca 1910” 2009.300.3277, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. |

1910 continued to provide gorgeous dresses in both day and evening wear, and tea gowns are no exception. The end of the S-silhouette and a slightly higher waistline characterized this decade. Skirts and trains narrowed and shortened as the decade crept closer to the 1920s. Aestheticism began to lose popularity in terms of fashion, although some people continued to follow the philosophy. The 1910 Worth tea gown pictured above still has a hint of Aesthetic style sleeve and the waistline is beginning to rise.

Neoclassicism, incredibly popular in the early nineteenth century, came back full force in the early twentieth century. The way the fabric is draped on the tea gown (left) and the pattern screen printed in gold and silver are clearly influenced by the Ancient Greeks. As this is the late 1910s, the waistline is less defined and the train and skirt are shorter than the 1910 tea gown pictured above right.

The 1920s are known for their huge shift from long skirts and tight, feminine shaped bodices to short skirts and straight and loose silhouettes. So how did tea gowns respond to a style that already daringly threw older social norms out the window? The answer lies in Fortuny. Mariano Fortuny was a designer whose Delphos gown made headway in the 1910s and inspired the 1920s. He opened his house in 1906 and even patented the rolled pleating technique that is his trademark. Like tea gowns of the previous century, the Fortuny gowns were meant to be worn indoors. However, eventually these grew popular and the mainstream silhouette changed enough that these Greek-inspired gowns became evening wear staples.

|

| Fortuny Evening Dresses, ca 1920s |

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Evening Dress 1920s” 1980.170, Gift of Gloria Barggiotti Etting |

In the same way that tea gowns mimicked mainstream silhouettes, they were also reminiscent of the stylistic trends and art and social movements of their decades.

In the late nineteenth century, an interest in the eighteenth century rose.

This revival can be seen in the Watteau back and polonaise style dresses in the 1870s and 1880s. This influence is particularly seen in early examples of tea gowns since they were created at the height of this trend.

|

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown ca. 1900-1901.” 2009.300.2498, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum |

While this Tea Gown is an example from 1900-1901, the eighteenth century influences that dominated the earlier incarnations of the tea gown are still relevant here in the light, pastel shades and the floral pattern over fine stripes in the fabric.

|

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress 1925-49,” 2001.702a–c, Gift of Clare Fahnestock Moorehead. |

Ancient Greek influences dominated fashion in the 1910s and into the 1920s. The Fortuny gown pictured above with its draped, toga-like mantel, is an obvious example of the Ancient Greek style in the twentieth century.

|

| Maryland Historical Society, 1974.62.24, Gift of Mrs. William Hilles |

The draped neckline of Mrs. Williams Hilles’ 1919 tea gown has a similar feeling to the Fortuny gown above. As pictured on page 14, the drape of fabric and the diagonal, silk-screened pattern in neoclassical motifs are clearly influenced by Ancient Greece.

Liberty of London was inspired by the historicism, mentioned above, as well as the Aesthetic movement when creating the tea gown. The Aesthetic movement has no clear beginning, although its philosophy can be traced as early as the mid-nineteenth century. The term Aesthetic emerged in the 1870s. This movement was a response to the utilitarianism of the Industrial Revolution and emphasized natural forms, beauty, truth, and “art for arts sake.”

This movement was met with heavy criticism in its early years, and was considered a counterculture. However, as Aestheticism gained note-worthy supporters, it became more – if not wholly- accepted by mainstream culture by the 1890s.

So, what exactly is Aesthetic, or artistic, dress? As stated by Lydia Edwards in her academic work, How to Read a Dress, “[a] desire for naturalness and less restriction, influenced by the designs of William Morris and Liberty’s London, was propagated by Oscar Wilde and his Aesthetic Dress Movement[…]and the emphasis was on soft velvets and loose gathering to create less structured clothing based on historical examples (partially medieval)”[1]. The tea gown pictured below captures the Aesthetic movement’s idea of medieval fashion with its high, flared neckline (called a Medici collar) and heavily gathered sleeves. By the 1890s, along with the Aesthetic movement, artistic dress styles wove their way into mainstream fashion.

|

|

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress, 1891” C.I.68.53.9, Gift of Mrs. James G. Flockhart | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress, 1890s” 1986.115.5, Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Trust Gift |

There seems to be some debate among sources as to whether tea gowns are a part of the radical dress movement. Some say yes, citing their loosened silhouette, the option to wear them without a corset, and their inspiration from the Aesthetic movement.

Other sources say that while these gowns fit much of the criteria for reform dress, the option to wear a corset and petticoats makes them less a part of the reform movement. Another point is that tea gowns were not necessarily created with the Reform Dress movement in mind the way that other forms of reform dress were. Either way, when the reform dress movement hosted an exhibit in the 1890s showcasing the possibilities of radical dress and their improvement of health, the House of Worth actually donated a tea gown to be exhibited for the cause.

|

| Maryland Historical Society, 1951.29.2, Gift of Mrs. Edwin Broyles |

The radical dress movement was not only a response to the health concerns of women’s fashion, but also to the changing roles of women in the nineteenth century. More and more women were entering the workforce and athletic activities and, therefore, the image of an athletic woman became popular. This necessitated the need to move more freely than tight corsets and long skirts allowed.

Prior to this, oftentimes women’s roles took place inside the home. Hosting events such as balls and dinners and maintaining the household were where women dominated. Afternoon tea, an activity largely credited to Anna Russell, the Duchess of Bedford in the 1830s or 40s, was another such event. Teas were hosted by the woman of the house and were typically a time when she gathered with her friends in an informal setting. Tea required no invitation – a woman simply wrote her visiting hours on the back of her calling card when handing it over to friends or acquaintances. While teas were traditionally headed by female members of the household, men could attend teas as well. Because this was an informal event, full dress was not necessary. However, the presence of visitors meant that the wrapper was too close to underwear to be suitable, thus the need for the tea gown.

|

|

| Ladies Taking Tea. Joseph Scheurenberg. Date unknown. |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tea Leaves. William McGregor Paxton. 1909. 10.64.8. Gift of George A. Hearn. |

One of the most interesting parts of tea gown culture is that while they challenged the rules of dress, they were just as much a part of traditional Victorian life with their role in these afternoon teas. Once again, tea gowns live in the contrast between the traditional and the unconventional. On the one hand, there is a radical nature to a gown that liberates a woman from the tightly corseted confines of every day dress while she socializes in the safety of her own home with her friends.

But on the other hand, these gowns are a part of an activity that is well established in Victorian culture, and once these gain popularity, these gowns are a perfectly acceptable form of social dress – even if they are only worn inside.

The contrasting nature of the tea gown is further exemplified by the New Woman Movement. The New Woman is best described as, “an independent and often well-educated, young woman poised to enjoy a more visible and active role in the public arena than women of preceding generations”[5]. While the New Woman may not seem directly connected to tea gowns on the surface, both the New Woman movement and the tea gown were liberating for women. One in the philosophical sense and the other in the physical.

The tea gown is one of the first steps towards new, radical dress for women that allowed them to work and move in society like never before. The New Woman Movement guided women towards gaining independence and options outside of the home and marriage. Both tea gowns and the New Woman played similar roles in nineteenth century society: on the one hand they subverted and challenged the current social ideal but, on the other, as they gained popularity, they become a part of the idealized woman in mainstream society and their influence is seen well into the twentieth century.

Whether one views tea gowns as a radical, liberating new way for women to dress or a garment as traditional as tea time, these gowns have somehow been a part of every artistic and social movement since they were introduced in the 1870s. Women’s roles within society began to change during the late nineteenth century and the modern woman truly emerged in the twentieth century. Tea gowns were just as much a part of this change as the women who wore them.

Sources:

[1] Lydia Edwards, How to Read a Dress (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 190.

[2] Eleri Lynn . Underwear: Fashion in Detail. (London: V&A Publishing, 2010), 194.

[3] Ribeiro, Aileen. Clothing Art: The Visual Culture of Fashion, 1600 – 1914. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

[4] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Evening Dress 1902” C.I.37.44.1, Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/82655?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=8&ft=1900s+dress&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=16

[5] Buzwell, Greg. “Daughters of decadence: the New Woman in the Victorian fin de siècle.” The British Library. May 15, 2014. https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/daughters-of-decadence-the-new-woman-in-the-victorian-fin-de-siecle

Bissonnette, Anne. “Victorian Tea Gowns: A Case of High Fashion Experimentation.” Dress. 44, No. 1 (2018).

Bohleke, Karin J. Nineteenth Century Costume Treasures of the Fashion Archives and Museum 1800 – 1900. Shippensburg: Shippensburg University, 2010.

The British Library. “The Rational Dress Society’s Gazette.” https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-rational-dress-societys-gazette

Buck, Anne. Victorian Fashion. 2nd ed. Carlton, Bedford: Ruth Bean Publishers, 1984.

Burdett, Carolyn. “Aestheticism and decadence.” The British Library. March 15, 2014. https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/aestheticism-and-decadence

Edwards, Lydia. How to Read a Dress. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Library of Congress. “The Gibson Girl as the “New Woman.” https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/gibson-girls-america/the-gibson-girl-as-the-new-woman.html

Lynn, Eleri. Underwear: Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 2010.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown 1880s” C.I.46.63, Gift of Miss A. Gladys Peck. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/106974?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1880s+tea+gown&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Tea Gown 1885.” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158314

Setnik, Linda. Victorian Costume for Ladies 1860 – 1900. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2000.

Women’s Fashions of the Early 1900s. New York: Dover Publications, 1992.

Whitehead, Nadia. “Hight Tea, Afternoon Tea, Elevenses: English Tea Times for Dummies. June 30, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/06/30/418660351/high-tea-afternoon-tea-elevenses-english-tea-times-for-dummies

Image Sources:

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Les Fêtes Vénitiennes, 1716-20, Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/watteau-mysteries-rococo/

Ladies Taking Tea. Joseph Scheurenberg. Date unknown. http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=278475

Maryland Historical Society, 1951.29.2, Gift of Mrs. Edwin Broyles

Maryland Historical Society,1984.79.5, Gift of Mrs. Lawrence K. Harper

Maryland Historical Society, 1974.62.24, Gift of Mrs. William Hilles

Maryland Historical Society, 1954.154.6, Gift of Miss Mildred Watson

Maryland Historical Society. 1971.100.2. Gift of Ms. Margery Richardson.

Maryland Historical Society. 1948.93.5a. Gift of Miss Louisa M. Gary.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress, 1890s” 1986.115.5, Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Trust Gift .https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81510?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=8&ft=1890s+dress&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=5

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress 1890s” C.I.40.106.42a, b, Gift of Mrs. W. Bayard Cutting.https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/107186?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=8&ft=1890s+dress&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=15

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dinner dress, spring/summer 1909.” 2009.300.3223.

Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Roland A. Goodman, 1961. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158137

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress, 1891” C.I.68.53.9, Gift of Mrs. James G. Flockhart. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81527?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1880s+tea+gown&offset=40&rpp=20&pos=60

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Dress 1925-49,” 2001.702a–c, Gift of Clare Fahnestock Moorehead. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/83312

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Afternoon Dress, ca 1875,” 2009.300.1100a, b, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/155778?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1870s+dress&offset=60&rpp=20&pos=69

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Evening Dress 1920s” 1980.170, Gift of Gloria Barggiotti Etting. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81595

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown, 1875-80,” 2009.300.3856a–c, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158839?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1870s+tea+gown&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=38

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown, ca 1910” 2009.300.3277, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158196?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=8&ft=1910s+tea+gown&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=1

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Evening Dress ca 1880” 2009.300.654, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum.https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/159209?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1880s+tea+gown&offset=60&rpp=20&pos=62

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown ca. 1900-1901.” 2009.300.2498, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/157330

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”Robe à la Française. 1750–75.” C.I.54.70a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/83605

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1912. 2005.386. Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/123612?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=1920s+dress&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=32

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tea Leaves. William McGregor Paxton. 1909. 10.64.8. Gift of George A. Hearn. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/10.64.8/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tea Gown 1880s” C.I.46.63, Gift of Miss A. Gladys Peck. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/106974?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&deptids=62%7c8&ft=1880s+tea+gown&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Tea Gown 1885.” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158314